Listening to the Patterns That Loved Us First

Attachment, Anxiety, and the Long Arc from Survival to Soul.

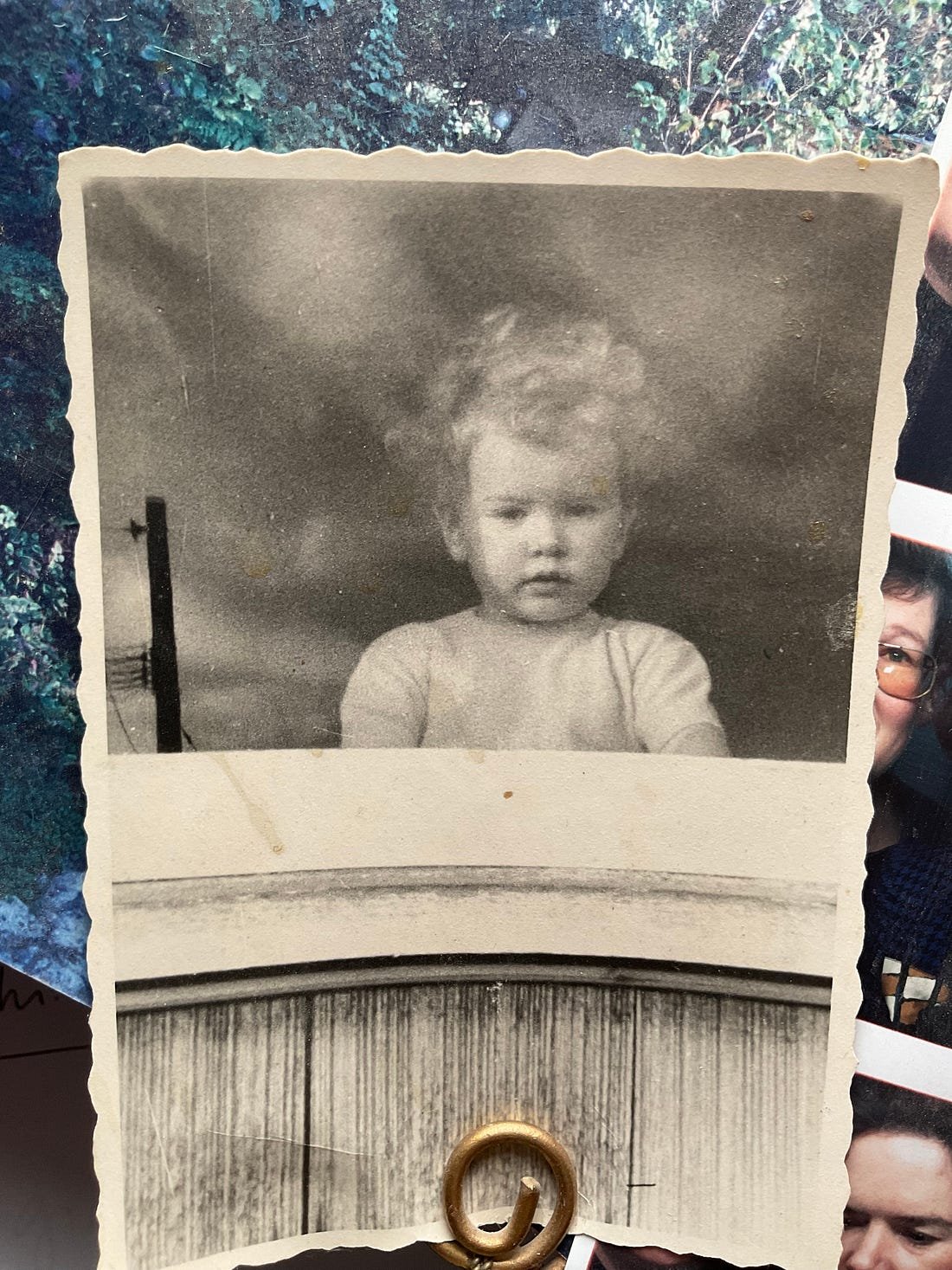

original photograph by Bren Littleton

There is a question that lives quietly in many of us long before we ever find language for it, a question that hums beneath our adult relationships and choices, shaping them in ways we do not immediately recognize. Why did I stay loyal to the parent who did not protect me?

It took me years to understand that this is not a moral question, nor a failure of courage or discernment, and certainly not evidence of some inherent flaw. There was denial at first, because denial is often how the psyche buys time until it has the capacity to see more clearly. In that sense, denial was not avoidance, but protection, a buffering that allowed life to continue while the deeper dynamics waited for the right moment to come into awareness.

Over time, and with work, that denial transformed into understanding. What had once been too much to hold all at once began to organize itself into meaning, into an understanding of why loyalty made sense, why attachment persisted, and why the child in me chose connection over safety. Awareness did not arrive as accusation, but as coherence, allowing compassion to replace confusion and self-blame to loosen its grip.

At its core, this question is rooted in attachment, because attachment, for a child, is not a preference or a choice, but a survival system.

As children, our nervous systems are wired for closeness, because proximity is how we receive food, shelter, comfort, and regulation. When a relationship is unsafe, unreliable, or emotionally confusing, the system often chooses connection anyway, since disconnection can feel far more threatening than enduring what hurts.

This is where ambivalent attachment takes root, where love becomes paired with uncertainty, care arrives inconsistently, and safety is partial or conditional. The child learns to wait, watch, adjust, and work harder for connection, not because the environment is healthy, but because the child’s psyche is adaptive, intelligent, and deeply committed to survival.

What often follows is the gradual development of coping strategies, not as flaws or pathologies, but as necessary responses to an environment that could not be trusted to hold the child consistently. These strategies form quietly and early, and they tend to become so familiar that we mistake them for personality.

Perfectionism is one of the earliest of these strategies, quietly forming around the belief that if I do everything right, if I am careful enough or flawless enough, then perhaps I will be safe. Over time, that inward pressure often flips outward as criticism, so we hold ourselves to impossible standards while feeling frustrated or irritated when others fail to meet them, even though these two behaviors are not opposites at all, but equal expressions of the same anxious vigilance.

Another common strategy is the need to be right, or the need to control, which can easily masquerade as competence, leadership, or strength. Beneath that drive often lives a fragile relationship with trust, trust in others, trust in ourselves, and under that an even older layer of experience, the chronic holding pattern formed in childhood when safety was unpredictable or absent.

And then there is the coping strategy most people want to eliminate, manage, or defeat: anxiety.

I have come to understand anxiety not as a flaw, but as one of our most faithful allies. Anxiety is the nervous system’s way of saying that something needs attention. It gets louder not to punish us, but because we are not listening yet. It alerts us when we are misaligned, overextended, silenced, or living too far from our truth.

When we try to suppress anxiety, we often miss its intelligence. When we turn toward it with curiosity, it becomes a guide.

Seen through a somatic and relational lens, anxiety arises when core needs have gone unmet and stress has been carried in the body for too long without resolution. This understanding is central to the work of Gabor Maté, who reminds us that anxiety is not random or defective, but deeply relational, shaped by early environments where vigilance was necessary in order to remain connected and safe.

From a depth-psychological perspective, symptoms are not merely problems to be solved, but messages asking to be received. This view is echoed in the work of Marion Woodman, who understood anxiety as an expression of soul seeking embodiment, a signal that something essential has been neglected, disowned, or split off, and is now asking to return to consciousness through the body.

This same orientation runs through Jung’s psychology, where symptoms are understood not as enemies, but as communications from the unconscious. What is ignored does not disappear; it lives on in patterns, repetitions, and bodily distress, asking to be known. Anxiety, in this sense, is not the problem. It is the messenger.

The more we attempt to control life, relationships, and outcomes in order to quiet anxiety, the more we believe we are preventing danger. Yet the psyche is honest and the nervous system keeps its own accounting, so what is often recreated instead is a relentless loop of hypervigilance, cortisol dumping, and internal tension.

Over time, the home, the workplace, friendships, and even intimate partnerships begin to feel tight, strained, and subtly pressurized. Chaos, in this sense, does not mean we failed; it means the strategy has reached its limit.

From a Jungian perspective, these patterns are not mistakes or misfires of development, but purposeful repetitions. The unconscious does not repeat in order to punish us; it repeats in order to be completed.

It returns us again and again to familiar emotional landscapes until we are able to see clearly, feel honestly, and choose consciously. What looks like regression is often the psyche asking for integration.

This is why coping strategies, including anxiety, often grow louder rather than quieter with time. They intensify because they are trying to get our attention, urging us to turn toward what we once dismissed, minimized, or gaslighted in ourselves.

They also ask us to re-home the orphaned moments where we split off from what we could not control, soothe, or make safe as children. Trauma, after all, is not only what happened to us, but what our nervous systems had to organize around in order to preserve attachment.

When these split-off places are finally seen, heard, and accepted, something profound occurs. Their need for our attention is complete, their work finished, and the body is finally able to exhale.

Relief arrives not through effort or fixing, but through recognition and integration. The system softens because it no longer has to protect what is being held.

This is where I diverge from the language of breaking patterns. Breaking implies force, rejection, or violence against the psyche.

What I witness again and again is that real change comes through acceptance, through thanking the pattern for what it gave us, for how it kept us alive, and for how it carried us through what we could not leave. Anxiety included.

In doing so, the pattern no longer needs to dominate our lives. Instead, it can rest, retire, and take its place as an elder within the inner council, holding wisdom and discernment, available when needed, but no longer directing our days.

This understanding also sheds light on why many of us have more than one significant partner across a lifetime, often two and sometimes three. Not because we failed the first time, but because it takes time to recognize that something different is possible.

It takes time to feel the distinction between intensity and intimacy, to separate attachment from love, and to hear the quieter voice of the soul beneath the old survival alarms.

As we move through anger, grief, and resentment toward our parents, without bypassing or diminishing what was lost, something begins to soften. The past does not become acceptable, but it loosens its grip.

We learn to hold complexity without self-betrayal, including the truth that a parent may have loved us deeply and still not protected us, having been frightened, dissociated, dependent, or trapped in their own unresolved trauma. Understanding does not erase impact, but it does release the nervous system from endless self-blame.

And when compassion finally turns inward, everything changes. The way we live with ourselves becomes the template for how we love others.

We give to our partners what we give to ourselves. When we offer ourselves patience, steadiness, boundaries, and care, we naturally begin to want a new pattern of love.

This new pattern is not rooted in vigilance disguised as devotion or caretaking as proof of worth, but in mutuality, safety, and presence that does not require performance.

And as we change in this way, some relationships cannot come with us. If others remain committed to older forms of relating, they may not be able to meet us, stay with us, or even want us anymore.

This is not failure; it is differentiation. We move on not because we are ungrateful, but because the old pattern is complete.

Benediction

May you learn to listen to your body as carefully as you once listened for danger.

May your breath become a place of orientation, your nervous system a trusted ally rather than a battlefield.

May what once protected you now guide you gently, without urgency or fear.

May you live with direction that arises from within rather than pressure imposed from without.

May creativity find its way back into your days, not as performance, but as expression.

And may hope return quietly, the way safety does, when it is finally allowed to stay.

Your patterns have loved you well.

You are now free to love differently.

written by Bren Littleton

original photograph by Bren Littleton

Tin Flea Press c. 2026