A Lesson in Writing

In a time when AI drafts paragraphs in seconds, here is a return to an old-fashioned form of the art of writing—built by hand, shaped by thought, and guided by a structure used for generations.

photo: personal correspondence/B. Littleton

Introduction to the Persuasive Argument Template

Over my thirty years of teaching writing, from creative to white papers to graduate level academia, I learned that many students came to their writing with strong ideas and subject expertise, but without a clear process for translating those ideas into an organized, persuasive written form. They could think deeply, but when faced with the task of producing academic essays or, ultimately, their thesis, they often struggled with structure.

To address this, I developed a simple yet flexible Persuasive Argument Template. It is a foundational guide that walks students through the architecture of a well-formed essay, from capturing the reader’s attention to presenting main ideas, addressing counterarguments, and building toward a meaningful conclusion. At first, students use the template to complete basic essays for their other classes, gaining confidence in sequencing their ideas. Over time, they learn how to expand and adapt the structure to handle the complexity of a thesis or dissertation.

The template works because it acts like the frame of a house: it holds the shape while the writer builds the interior. It does not dictate the writer’s style or limit creativity; rather, it supports clarity and coherence so that the ideas can breathe. Once students internalize this architecture, they can move beyond it, experimenting with voice, layering nuance, and developing a more sophisticated flow of thought.

As a living example of how this template functions, the essay that follows, on the art of writing itself, has been built directly from its structure. In it, you will see each element of the template brought to life, not as an outline of instructions, but as a full expression of ideas, arguments, and personal reflection.

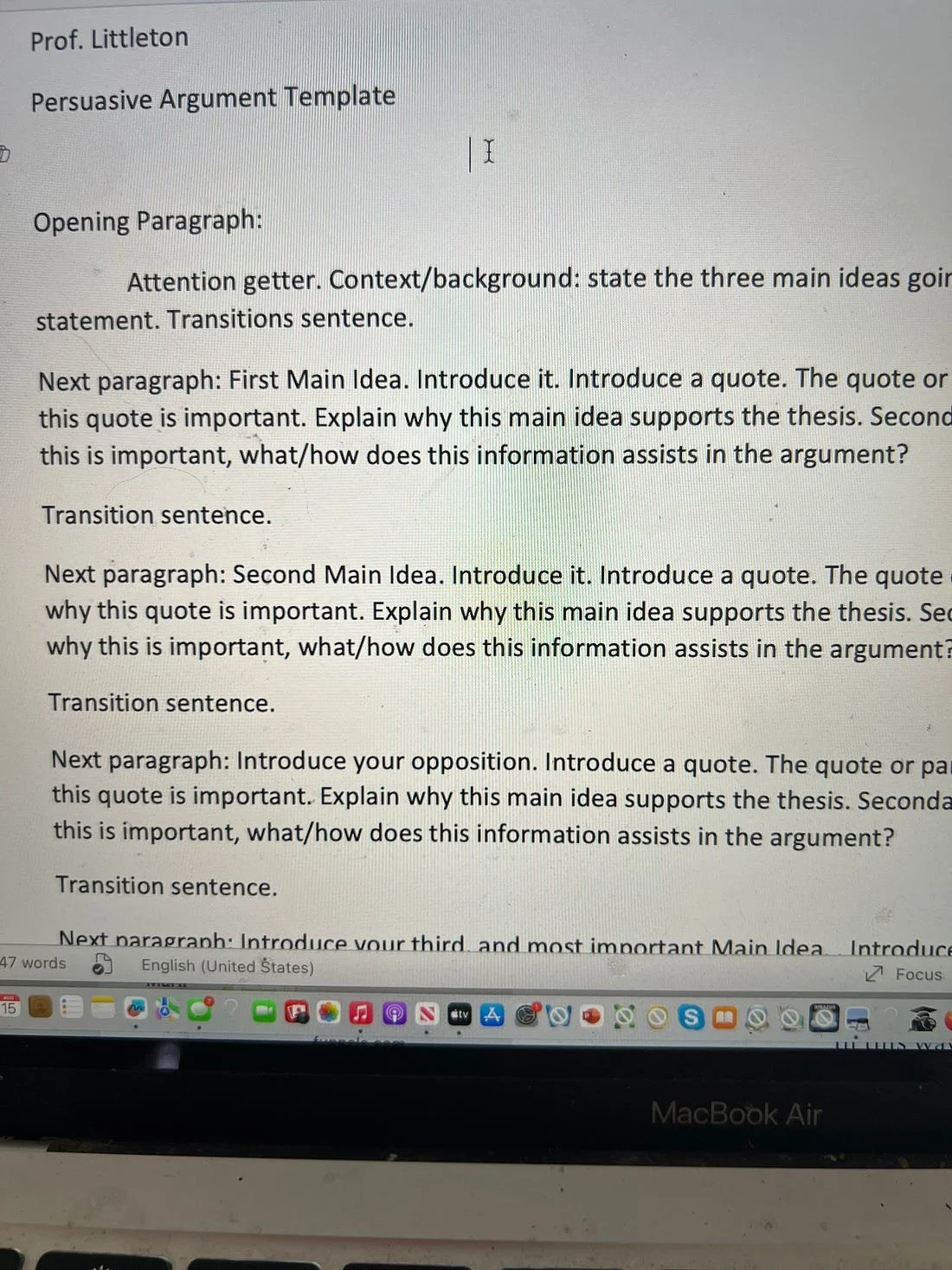

Persuasive Argument Template

Opening Paragraph:

Attention getter. Context/background: state the three main ideas going to be discussed. Thesis statement. Transitions sentence.

Next paragraph: First Main Idea. Introduce it. Introduce a quote. The quote or paraphrase. Explain why this quote is important. Explain why this main idea supports the thesis. Secondary detail. Explain why this is important, what/how does this information assists in the argument?

Transition sentence.

Next paragraph: Second Main Idea. Introduce it. Introduce a quote. The quote or paraphrase. Explain why this quote is important. Explain why this main idea supports the thesis. Secondary detail. Explain why this is important, what/how does this information assists in the argument?

Transition sentence.

Next paragraph: Introduce your opposition. Introduce a quote. The quote or paraphrase. Explain why this quote is important. Explain why this main idea supports the thesis. Secondary detail. Explain why this is important, what/how does this information assists in the argument?

Transition sentence.

Next paragraph: Introduce your third, and most important Main Idea. . Introduce it. Introduce a quote. The quote or paraphrase. Explain why this quote is important. Explain why this main idea supports the thesis. Secondary detail. Explain why this is important, what/how does this information assists in the argument?

Transition sentence.

Next paragraph: Conclusion. What has been developed/learned? Restate the thesis, and review the three main ideas. Provide a sentence or two about the growth, or the value of the argument, and why it solves a problem.

The Example: Let’s see how this template lives is real life!

The Art of Writing: A Lifelong Conversation with the Self and the World

Writing is not just about putting words on paper. It is about discovering who we are while finding the courage to share it. For centuries, authors have described writing as a practice of showing up for oneself, as much as for the reader. It is a craft, a discipline, and, in many ways, a spiritual practice. Toni Morrison once said, “If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.” Morrison herself began her first novel, The Bluest Eye, while working full time and raising two children, often writing in the early mornings before her household woke up.

For me, writing has always been more than craft or profession. It is my constant companion. It is the place I go for safety and comfort, a trusted space where I download guidance from the unconscious. Like Jung’s Philemon, a similar guide named Airabus appeared to me when I was a child. Airabus translated ephemeral pockets of meaning into language I could grasp, poems, long shoreline observations, the sounds of waves, ancient spells and old recipes, the daily chores of faeries and the fey. These filled dozens of thin, hardbound journals. Over time, I learned that writing was not just a tool for expression, but a way to map the unknown territories of the psyche and tether myself to the present moment.

In this essay, we will explore three core ideas about writing: writing as a daily practice of self-discovery, writing as an act of permission and courage, and writing as a transformational dialogue between the inner and outer world. Along the way, we will also address the myth that writing is primarily a technical skill, a myth that can keep people from embracing the fullness of their creative voice.

First Main Idea: Writing as a Daily Practice of Self-Discovery

Writing reveals us to ourselves. Natalie Goldberg, in Writing Down the Bones, urges us to treat writing like a daily meditation: “Write every day. Write as if you are dying.” She tells the story of committing to write in coffee shops for hours at a time, filling notebook after notebook with raw, unpolished words. It was in the rhythm of daily writing, not in isolated flashes of inspiration, that she discovered her voice.

Julia Cameron’s The Artist’s Way reinforces this with her “morning pages” practice, three longhand pages written each morning to clear the mind. Cameron developed the practice when she was blocked in her own screenwriting, realizing that before she could write anything good, she had to write out the noise.

In my own life, daily writing began as a child’s instinct and became an adult’s discipline. As a girl, I wrote not to “become a writer” but to steady myself, to see what I thought, what I feared, what I hoped for. Over time, those notebooks became a record of my inner landscape, a mirror that revealed changes I could not yet name.

Ray Bradbury wrote every single day for decades, producing over 400 short stories, dozens of books, and countless essays. “You must write every single day of your life,” he said, because that is how you stay close to the source of inspiration. Writing daily is not only about output, it is about anchoring yourself in a dialogue with the self.

Transition: Yet showing up is only part of the journey; we also need permission to be imperfect.

Second Main Idea: Writing as an Act of Permission and Courage

Many aspiring writers freeze not because they lack ideas, but because they fear judgment, their own and others’. Anne Lamott, in Bird by Bird, offers the famous advice: “Almost all good writing begins with terrible first efforts. You need to start somewhere.” Lamott admits she often writes “awful first drafts” to bypass her inner critic and find the heart of her story.

Stephen King warns in On Writing that perfectionism is the fastest way to kill creativity. He recalls working on Carrie in a trailer, nearly abandoning it before his wife rescued the pages from the trash. Without her encouragement to keep going, the novel that launched his career would have been lost.

Zadie Smith has said she spends the first year of a novel “just listening” to her characters, not worrying whether the writing is good. I have seen this same truth in my own students: the moment they stop trying to impress and instead allow themselves to explore, their writing becomes alive.

Ursula K. Le Guin believed in craft honed over time and was candid about how her early work borrowed heavily from others. I relate to this, my first academic writings were saturated with too much description, heavily influenced by D. H. Lawrence, James Joyce, and Alice B. Toklas. I had to learn that less could indeed be more. Courage in writing is often the act of releasing the performance and returning to the truth.

Transition: Of course, some may argue that writing is primarily a technical skill, something you master with rules, grammar, and structure.

Opposition: The Myth that Writing is Only a Technical Skill

It is tempting to think that once you learn grammar, sentence structure, and storytelling techniques, you “know” how to write. Catherine Ann Jones, in The Way of Story, warns against reducing writing to mechanics: “Structure is important, but without soul, the story will not breathe.”

Toni Morrison began not with plot outlines but with a voice or image that haunted her. Mary Oliver wrote from her daily walks, capturing small observations that carried large truths. Neither approached writing as merely a technical act; they approached it as a form of listening.

Technical skills are important, they give writing clarity and coherence, but they are not the heartbeat of the work. Henry Miller spoke of “the willingness to look stupid,” and in my own teaching I have seen how this willingness frees writers from paralysis. Grammar will not save a story without the courage to say something real.

Transition: Which brings us to the most vital truth: writing is not just a skill or an act. It is a transformational conversation between our inner life and the world around us.

Third Main Idea: Writing as a Transformational Dialogue Between the Inner and Outer World

When we write, we are in conversation, sometimes with ourselves, sometimes with an imagined reader, and sometimes with life itself. Stephen King calls writing “a telepathy,” a way of sending thoughts and experiences across time and space.

Henry Miller saw writing as a voyage of discovery. Zadie Smith views it as a lifelong dialogue with the self. Ursula K. Le Guin urged writers to listen “for the voices under the voices.” Mary Oliver’s call to “pay attention, be astonished, tell about it” perfectly captures the bridge between perception and expression.

For me, writing has always been about locating myself in the Now, recording the topography of my inner life as it shifts. Over time, I have come to see teaching writing as an extension of this dialogue, offering my students not only the practical “spells” for success but also the keys to the subtler magic that links our individual stories to the long human thread. The template I created, and which structures this essay, is more than a tool for organization. It is a map, a key, a code for finding one’s way into the writing life.

Conclusion

The art of writing is more than a talent. It is a practice, a permission, and a dialogue. We have seen how daily writing builds self-awareness, how granting ourselves permission to write badly frees us from perfectionism, and how writing as a dialogue with life connects our inner world with the outer one. We have also challenged the idea that writing is purely a technical skill, recognizing instead that great writing blends craft with courage.

Julia Cameron reminds us that “Leap, and the net will appear.” Anne Lamott reminds us that “Perfectionism is the voice of the oppressor.” Mary Oliver reminds us that attention itself is a form of love.

Together, these writers and the many who came before them teach that the voice you need is already within you. The only task is to sit down, listen, and write.

Closing Reflection on the Template in Action

The essay you have just read follows the Persuasive Argument Template step by step, demonstrating how a clear structure supports the expression of complex ideas. The opening paragraph introduces the topic, sets context, and presents the thesis. Each main idea is developed in its own section, supported by quotes, examples, and explanation. An opposition paragraph addresses a common counterargument, showing how the writer can anticipate and respond to alternative perspectives. The third main idea builds toward the most important insight, followed by a conclusion that ties the ideas together and offers a final reflection.

While this essay stays true to the template’s architecture, it also expands on it, layering in multiple author voices, personal narrative, and nuanced connections between concepts. This is precisely how the template is intended to work in academic writing. At first, it serves as a map for organizing thought. Later, as the writer grows in skill and confidence, it becomes the foundation upon which to build an original, fully developed work, whether a course paper or a graduate thesis.

In this way, the template is not a cage for creativity but a framework for clarity, helping writers shape their ideas into a coherent, persuasive, and ultimately compelling expression.

written by Bren Littleton

photo: personal correspondence/B. Littleton

Tin Flea Press c 2025